Soap Culture History III - From the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution

22-06-2023

10:31

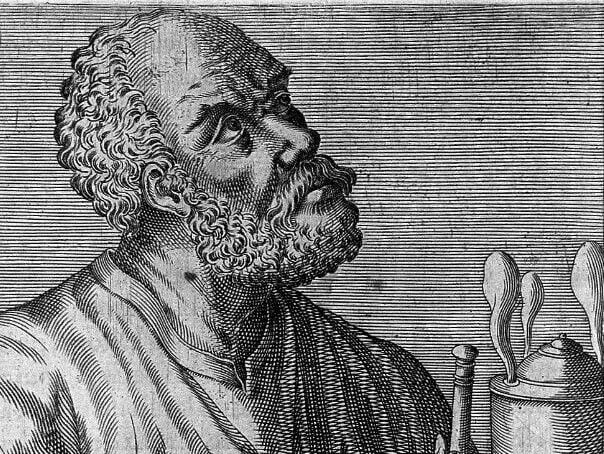

Cabir bin Hayyan; (A.C. 721-813), Muslim scientist, his written works on chemistry, alchemy, astronomy and philosophy were translated into Latin under the name of "Geber Collection". There is a consensus that a part of the corpus was written by his followers after him. The name "Geber" is the Latinized form of Jabir. The translations were made by a Spanish writer almost 500 years after his death. His practical instructions on laboratory procedures in his four books, which are believed to have been written during his lifetime, are indicative of his well-deserved reputation in the history of chemistry.

A.C. In the 8th century, the use of soap as an effective cleanser is documented in the writings of the Arab alchemist "Jabir Ibn Khayyam", who is considered the "father of alchemists". Alchemy; It was a trial-and-error endeavor with dubious theoretical foundations, where measurements were not in question. It cannot be considered a science as it does not provide systematic knowledge. However, the alchemists of the past were the pioneers of the transition to chemistry and designed many laboratory instruments used even today. At that time when Islamic thought was on the rise, Muslim alchemists produced a kind of soap that could be described as "soap" in the sense we understand it today, in which olive oil and other vegetable oils were used. Palastin (Nablus), Kufa and Basra from Middle East cities Soap production began in the 7th century. The recipes used in the production of soaps, some of which are solid and some of which are liquid, have continued to be used almost unchanged until today. Arab soap makers enriched their production culture by adding perfume and colorants to their soaps. Gene M.S. In the 8th century, Moroccan chemist Al-Razi documented an elaborate recipe for making hard soap consisting of sesame oil, potassium hydroxide, and lime.

In the archaeological excavations in the Middle East geography, A.C. Remains of soap mills dating back to the 9th century were found. It was understood that soaps containing potash (potassium-rich salts) and water were produced, consisting of a mixture of ash obtained by burning the sea bean plant and olive oil.

A.C. In the 10th century, in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, the soap manufacturing industry multiplied to the point of establishing a guild. The document named "The Book of the Eparch/Prefect - The Governor's Book" (Byzantine commercial handbook) does not contain the recipes used in production, but contains many details about the laws and regulations in the soap production sector in the city. In the empire, the import of soap was prohibited in order to protect the producers, and the yellow soap produced for the palace was not accessible to the public.

There is a general consensus that soap consumption decreased among medieval European peoples. During the Roman Empire, when polytheistic belief was widespread, there was a widespread cleansing and bathing culture that people with pagan beliefs brought to life before worship and in daily life. It is claimed that the reason for this was a policy implemented by the Papal institution with the rise of the idea of monotheism. The aim was to distract them from the ritualistic pagan practices of washing and cleansing, and to make the polytheistic peoples with a consciousness of cleanliness forget their old beliefs.

With the rise of Andalusian culture, soap production – now as a craft – begins to become widespread in the Mediterranean coastal cities of Venice, Genoa and Marseille.

Soap manufactures A.C. In Venice in the 14th century, AD. They become widespread in the Castile region in the 15th century. The soap produced in these soap shops was probably the first white hard soap. It became popular as "Castile soap". The most important raw material of soaps made in these cities is olive oil. In these periods of history, thanks to the policies followed by the Roman Empire in the previous centuries, olive agriculture and olive oil production became widespread throughout the Mediterranean basin, and innovations in olive oil production technologies increased olive oil production. Thus, it became easier to obtain olive oil as a raw material used in soap making, and the speed of soap production increased.

A.C. In the 9th century, many soap shops appeared in Marseille, producing soap. It has also been claimed that the soap-making culture in Marseille was brought by the Phocaeans, who were the first Ionian sailors who had immigrated there and made long sea voyages, but this claim is controversial.

A soap making recipe, in the sense we understand it today, more detailed than what has been done before, is A.C. It will be documented in the book "Mappae clavicula" in the 12th century. The book is a medieval Latin text containing craft materials and production recipes from materials. Here it is described how artisans use soap in the fabric washing process and as a soldering material. Solder soap is obtained from a mixture of copper and a dye called 'Calcothar'. As it turns out, it is not easy to find the soap produced with this recipe, olive oil is used in its production.

At that time, Spain was one of the geographies where the most olive cultivation was done on the Mediterranean coast, one of the recipes in the book is similar to "French/Marseille soap", red colored fruits are used to give the red color. The behavior of giving red color to soapy melts is a Gallic culture from earlier times. According to the Roman naturalist Plinius (24-79 AD), this habit came from the desire of Gaul men to give their hair a "tint close to red". Plinius relates that Gaul men who lived in today's French lands applied a kind of soapy plum made from red ash and beef fat to their hair. The idea that having red hair was a "symbol of sexual desire and vice" in the medieval religious European consciousness was perhaps a legacy from the Romans' view of the Gauls as barbarians.

At the end of the 12th century, Venetian soap makers became popular with the soaps they produced with the "usnan" (serpentine, celandine) imported from Syria and Egypt, and they began to compete with the soap makers of Marseilles origin. The quality, white and fragrant soaps they produce thanks to olive oil are a product that is exported to Southern Germany, the ports of the Western Mediterranean, the Muslim Levant, and many places including Anatolia. The leadership of the Venetian soap manufacturers in the Mediterranean market lasted for about 600 years, then the situation was reversed with the increase in production in Marseille.

Soap production was most developed in Germany in the Middle Ages. In the late 13th century, during the Charlemagne Empire, homemade soap production became widespread and soap making became a popular business.

The first English soap production probably begins in Bristol in the late 12th century. British soap makers develop soap production with different vegetable oils reaching London from their colonies all over the world. It is known that in the 12th and 14th centuries, a group of soap makers gathered at "Cheapside" in London. In the 16th century, gray soap with white spots and hardness is called "Bristol Gray Soap", it was sent to London in large quantities until 1523 and provided the need of the capital. The British imported "Castile/Castile Soap" from Castile in the 17th century, as the coarse, poor quality, black and soft "Bristol Soap" produced by the British themselves from train oil was not suitable for washing clothes. In 1622, a soap tax was introduced in England, a law was passed requiring producers to "produce at least 1 ton of soap", but huge boilers were required to meet this criterion, small producers who did not have these boilers could not produce soap, soap production became monopolized.

It has now reached the times when soap, which is described as "natural" or "traditional" in the sense we understand today, was made. Traditional soap formula and making techniques have been standardized. Clay water, vegetable or animal oil, especially olive oil, and rock salt are used. No synthetic compounds or dyes are used. The laurel tree, which is a common species in the Mediterranean geography, is frequently used to give essence to soap.

Ottoman Empire Geography

The olive tree, as a naturally occurring tree in the Mediterranean basin climate, is a natural source for soap production due to the rich oil contained in its fruit. Olive oil, laurel and menengiç (çitlenbik) soaps are very common in this geography. These three plants are the main determinants of the Mediterranean geography. As olive agriculture spread and multiplied, soap shops where production was carried out increased, and soap became an economic object traded in time. In the historical process, small or large scale soap shops have emerged in many settlements where olive production is common. In Anatolia, in the Southeastern Anatolia Region; In the centers of provinces or districts where olive production is made, in areas where trade is intense, many soap shops will emerge, which are an indicator of urban identity.

On the Anatolian coast, where the olive tree is grown abundantly, soap production becomes widespread. During the Ottoman Empire, as a line of business coming from the Eastern Roman Empire, production was carried out in soap shops of various sizes in various parts of the empire. Over time, a wide variety of soaps emerge, depending on the place and quality of production; Tripoli soap, Cretan soap, Iraqi soap, Heraklion soap, black soap, pasha soap, musk soap, sultan's soap... In this sense, in the entire Aegean and Mediterranean coastline from Edremit to Nizip, and in Aegean islands, especially Lesbos and Crete. In the Middle East, soap shops emerged, especially in the city of Nablus. For example, while approximately 2 million tons of olives were harvested in Antakya, more than 1 million 650 thousand tons of soap were produced in historical records. Crete shows a significant development in both olive oil and soap workshops. Crete, which is the most rooted island in terms of olive oil culture history, produced the best quality and sought-after soaps of the Ottoman Empire (Heraklion soaps). The number of soap workshops on the island of Crete, which was six in 1723, reached twelve in the 1750s and eighteen in 1783.

While soaps produced in Western Anatolia and the Islands have an important share in meeting the annual soap need of Istanbul, soaps produced around Aleppo, Nablus and Damascus have been exported mostly to Europe as well as meeting local needs. The musk and fruit soaps produced in Edirne, especially by Greek soap makers, have a special place. Musk soaps are among the gifts presented to the palace. On the navel stone in the bath, soaps that do not melt immediately, are foamy and do not leave any stains or traces on marble surfaces when melted are preferred. Evliyâ Çelebi's Seyahatnâme contains details about soap and soap shops in the Ottoman geography, although the authenticity of his stories and observations is debatable.

Compiled by: Uğur Saraçoğlu (mustabeyciftligi@gmail.com)

Resources:

1. A Special Example from Turkish Cultural Geography: Turkish Soaps, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, October 2019, Dr. Güven Şahin, Istanbul University Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Geography.

Resources:

1. A Special Example from Turkish Cultural Geography: Turkish Soaps, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, October 2019, Dr. Güven Şahin, Istanbul University Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Geography.

3. Natural Laurel Soap; Tahsin Ozer, Fatma Zehra, Ali Ihsan Ozturk,

ALKU Journal of Science, ALKU Journal of Science 2021, Issue 3(2): 29-37 e-ISSN: 2667-7814.

5. Soap Shops in Turkey; Müge Çiftyürek, PhD Thesis, Art History Department, Art History Doctorate Program, Pamukkale University, Social Sciences Institute, 2021.

6. https://gorgondergisi.com/kizilsackorkusu/.

6. https://gorgondergisi.com/kizilsackorkusu/.